I see it all the time. A charitable nonprofit organization spends a lot of money on a consultant to shepherd them through a traditional strategic planning process, only to end up watching the organization continue on the same trajectory of mediocrity or slow decline. Or perhaps conditions change that significantly alter the operating environment and the once hoped-for vision of the future is jettisoned in order to address more immediate concerns. Or worst of all, a beautifully crafted, four-color strategic plan dies on the shelf because the organization lacks the tools, leadership, or resources needed to turn the plan into action.

One could rightly ask, why even bother? If you can’t expect demonstrable improvement in either mission impact or financial sustainability, why go through the rigors of strategic planning? All too often, strategic planning is nothing more than an academic exercise, consuming human and financial resources, with little to show for it at the end of three or five years. It’s no wonder that some CEOs hate having to go through it.

The last thing I will tell you is to give up on strategic planning. But I will also quickly add that the process, as it has been developed and practiced in recent decades, is inherently flawed and limited. I say it is flawed because it often is based on either false or untested assumptions about the future. And I say that it is limited or incomplete because strategic planning as a discipline is not dynamic enough or conceptually robust enough to respond to changing conditions. Finally, most strategic plans fail to articulate and measure strategic actions that can substantially “bend the curve” of performance to achieve the overall vision.

Every organization should have a vision for the future. It should be bold and challenging. It should have the capacity to direct action. The exercise many organizations go through, however, once a vision or strategic position has been identified, is to “back-cast” from the vision to articulate the intermediate actions that are required to move the organization toward that vision. Sounds logical. But every one of those intermediate steps is based on the assumption that the vision will be as relevant five years from now as it is today. All I need to do to dispel that notion is to say the date: “September 2008!” Who could have anticipated the far-reaching impact of our country’s economic recession? And how many of us (and I include myself) were guilty of having constructed strategic plans in the months prior based on assumptions of continued growth? So at the outset, let’s agree that setting a vision or strategic position that describes with a high degree of accuracy (or arrogance) what the organization will look like in three to five years is imprudent to say the least.

Let me share what I have learned about strategic planning over the years and suggest that there might be a better way of doing things. At the heart of this approach is the word continuous. The days of crafting a strategic plan with a three or five-year horizon that is going to serve as the “bible” for action over that time period have to be over. To think that such a plan is sufficient to direct strategic decision-making over such a long time period in today’s fluid environment is ludicrous. Having said that, I do still believe in writing strategic plans that have a three to five-year horizon. Hypocritical? Self-contradictory? Not at all. Let me explain.

Because the strategic planning process, when done well, engages a broad spectrum of stakeholders, repeating this strenuous activity more frequently than every three years would be exhausting. I am a strong advocate of tearing the plan down to the ground and starting over every three to five years. The larger the organization, the farther the horizon. Small organizations have fewer moving parts and usually more narrow missions and are more capable of managing the planning process without disruption of services. Regardless of the size of organization, how that plan, once completed, is used to guide the organization on a day-to-day basis and to actually effect change and achieve the preferred future described therein – ah, there’s the rub! And therein lie the keys to effective planning as well.

So what’s missing in how strategic planning is typically conducted that leads to failure? What additional processes or functions need to be integrated into strategic planning to ensure continued relevance and success? What is the real purpose behind strategic planning and how can that goal be achieved without falling victim to the pitfalls described above? Following are a few of my thoughts in this regard about how to construct a strategic plan that can keep the organization focused on its vision, remain true to its mission, and still function in a strategically nimble manner as the operating environment undergoes change.

Process Determines Product. Many CEOs assign responsibility for leading the strategic planning effort to either a designated strategy officer if the organization is large enough (I was one of those!) or to a consultant who purports to know how to facilitate this process (I am now one of those, too!). Unfortunately, my experience has shown that many if not most consultants apply traditional processes extracted from the business world without really understanding the dynamics at work in the organization and its environment, nor do they equip the organization with the tools needed to operationalize the plan once it is completed. All too often they engage organizations in activities such as SWOT analysis or the aforementioned “visioning” exercise without questioning the rationale or the value of that activity. Likewise, I have found that just because a consultant is an excellent facilitator does not mean that he or she is current in the literature around strategic planning. The fact is that not all traditional strategic planning processes are appropriate for nonprofit charitable organizations and do not provide a template for nimble decision-making in a rapidly changing environment. More appropriate processes must be utilized if the desired result is a more relevant and effective strategic plan. Excellent alternatives to traditional models of strategic planning have been developed by McLaughlin and Allison and Kaye.

Process Determines Product. Many CEOs assign responsibility for leading the strategic planning effort to either a designated strategy officer if the organization is large enough (I was one of those!) or to a consultant who purports to know how to facilitate this process (I am now one of those, too!). Unfortunately, my experience has shown that many if not most consultants apply traditional processes extracted from the business world without really understanding the dynamics at work in the organization and its environment, nor do they equip the organization with the tools needed to operationalize the plan once it is completed. All too often they engage organizations in activities such as SWOT analysis or the aforementioned “visioning” exercise without questioning the rationale or the value of that activity. Likewise, I have found that just because a consultant is an excellent facilitator does not mean that he or she is current in the literature around strategic planning. The fact is that not all traditional strategic planning processes are appropriate for nonprofit charitable organizations and do not provide a template for nimble decision-making in a rapidly changing environment. More appropriate processes must be utilized if the desired result is a more relevant and effective strategic plan. Excellent alternatives to traditional models of strategic planning have been developed by McLaughlin and Allison and Kaye.

- The Plan Lives. Make the Strategic Plan the principal reporting and evaluation document of the organization. This can be accomplished in a number of ways. With respect to the Board of Directors, I would suggest dispensing with all customary operating reports and placing them into a consent agenda. I would structure the agenda of Board meetings around the Strategic Plan with progress reports focused only on the accomplishment of strategic objectives, and/or reports on alterations due to changing conditions. If you meet regularly with your leadership team (I used to hold weekly “huddles”), devote one longer meeting per month to review the strategic plan, performance data, and assignments related to accountability measures. Tactical challenges to achieving strategic goals and objectives might result in alterations to the plan. Such regularized formal executive review also holds individual leaders accountable for progress.

- Mission vs. Sustainability. Too often, organizations engage stakeholders in ethereal discussions about mission and vision without testing the financial viability of that mission. A good mission statement should describe the what, where, why, how and with whom questions. But mission statements are effective only if they can be translated into sustainable programs and services. Here is where many organizations go off the rails. Let’s face it. There are many wonderful things that need to be done in the world to serve and support others.

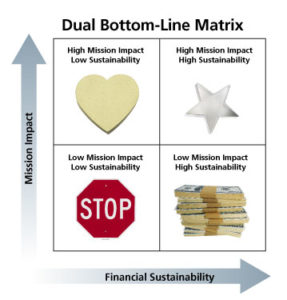

That’s what charitable nonprofit organizations exist to do. But not all of those wonderful services can be supported. In other words, they are not sustainable. I would argue that an organization’s mission must be continuously balanced against the concern for sustainability and that the time to do this is at the beginning of the strategic planning process. In a methodology developed by Bell, Masaoke and Zimmerman, the programs and activities that flow out of an organization’s mission should be rated with respect to two key factors: impact and profitability. As part of a thorough evaluation of mission, every nonprofit organization should ask itself whether or not each of its various programs and services are critical to the mission by having a large impact on the largest possible number of people, and whether or not those programs and services can be supported, either on their own, or with subsidy from other profitable areas of the organization. Allison and Kaye provide an excellent example of how such an analysis of the business model can be integrated into strategic planning.

That’s what charitable nonprofit organizations exist to do. But not all of those wonderful services can be supported. In other words, they are not sustainable. I would argue that an organization’s mission must be continuously balanced against the concern for sustainability and that the time to do this is at the beginning of the strategic planning process. In a methodology developed by Bell, Masaoke and Zimmerman, the programs and activities that flow out of an organization’s mission should be rated with respect to two key factors: impact and profitability. As part of a thorough evaluation of mission, every nonprofit organization should ask itself whether or not each of its various programs and services are critical to the mission by having a large impact on the largest possible number of people, and whether or not those programs and services can be supported, either on their own, or with subsidy from other profitable areas of the organization. Allison and Kaye provide an excellent example of how such an analysis of the business model can be integrated into strategic planning.

- Rolling Plans. Promote continuous and rolling adjustments to the plan to reflect changing realities. While I believe a three to five-year horizon is appropriate, I also believe that the staff should provide formal updates of the plan on an annual basis. In other words, the strategic plan should be a “rolling” three to five-year plan with the board of directors adopting each new annual iteration. In some smaller organizations, a new and updated “version” of the strategic plan could be presented at each quarterly board meeting. The point is that thinking in shorter time periods promotes continuous evaluation of progress, continuous scanning of the operating environment, continuous accountability by persons responsible for executing aspects of the plan, and continuous reporting to stakeholders. At the same time, I am not an advocate of having a perpetually rolling strategic plan. There is great value to periodically tearing the plan down to the ground and starting over, if for no other reason than to engage a broad spectrum of stakeholders in this critical “ownership” activity and to test the validity and viability of the vision, mission and core values statements.

- Business Intelligence. One of the biggest limitations I have observed is the lack of meaningful data which actually measures the performance of the organization in those variables which define the stated goals and objectives. Too often, a goal for growth is stated with no connection to the actual activities that will determine success or failure in achieving the goal. For example, a strategic goal might call for an increase of 20% in the number of people supported, but no data points are identified with respect to who that population might be, where they would come from, and which measurable tactical steps would be required to recruit and engage those possible clients. Having up-to-date information that informs the organization of its performance is absolutely critical to success. Increasingly, nonprofit organizations are realizing the need for robust business intelligence systems. In the past, only a very few nonprofit organizations could afford to build such data base management systems. Fortunately, new tools are available which have the potential to significantly improve an organization’s ability to access, manage, and effectively utilize data from multiple sources within the organization. One excellent example is the Microsoft product called “Power BI.” This tool is well supported, easy to use, and has a great deal of capacity for data analysis and reporting.

- Resource the Plan. Smart organizations will build their annual budgets around their strategic plan and will work with a planning/budgeting cycle that integrates the two processes. However, another shortcoming of many strategic planning efforts is the failure to consider the cost of executing the plan. While budgets may reflect anticipated revenue and expense from a new program, it is pretty rare to see an organization put a dollar figure to the human hours required to manage and execute the strategic plan. There seems to be an unspoken assumption that the current staff will absorb the responsibility for executing the planning initiatives within the framework of their existing hours and manpower. This “do more with the same or less” approach is destined to fail. The truth is that executing a strategic plan requires more attention, more review, more monitoring, more reporting, more planning, more leadership – in short, more of everything. Therefore, in addition to the added revenue and expense associated with new or expanded programs and services, the administrative costs to the organization should be incorporated into the planning process and included in operating budgets.

- Bias Toward Strategy. From the foregoing, it should be pretty evident that I am an advocate of continuous planning and evaluation. The episodic strategic plan can serve as the platform for such a dynamic approach, but only if it is viewed as a framework for continuous strategic decision-making. Leaders of charitable nonprofit organizations need to employ tools that promote strategizing, as opposed to strategic planning. Strategic thinking should be the stuff of every executive’s daily intellectual diet. How is it going? What’s changing? Where are we vulnerable? How effective are we? Who needs to be engaged? And a thousand more questions all focused on the current position of the organization in its current environment, moving on a trajectory toward achieving a vision requiring constant testing and refinement. Tools and resources which promote such thinking are not traditionally integrated into strategic planning processes. I think part of the reason for that lies in the fact that consultants are engaged to produce a product within a fixed number of billable hours. The “deliverable” is a nice looking, inspiring document that can be shared with donors, but which is usually devoid of any means for actually accomplishing the stated goals. Fortunately, some very good thought into this shortcoming is finding its way into the nonprofit world. An example would be David LaPiana’s very good book The Nonprofit Strategy Revolution. With an emphasis on strategy and execution, he provides methods and tools for leaders to turn away from planning as an end and toward strategy development and action.

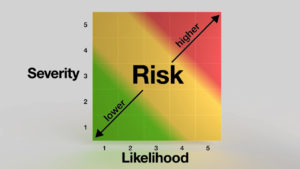

- Concomitant Risk Management. Finally, the best strategic plan in the world cannot prepare an organization to deal with the devastating effects of a national economic meltdown, a natural disaster, criminal activity by employees, loss of a donor-database, or any of a hundred other catastrophes that can and do befall nonprofit organizations. In the wake of Enron and Sarbanes-Oxley, many nonprofit organizations have beefed up their board audit committees to include ethics and risk assessment. A few have even developed tools for monitoring key risk factors and assigning key staff to lead risk mitigation teams in an effort to minimize both the likelihood and negative impact of various types of risk.

I would strongly encourage every nonprofit to seriously attend to this issue, and if lacking in knowledge or expertise in this regard, hire someone to facilitate that process. The point I wish to make here is that I have not seen any nonprofit organization integrate risk assessment into its strategic planning process. And by this I do not mean conducting a SWOT analysis. I do not consider weaknesses and threats, per se, to necessarily be risks to the organization. They are factors to be managed, certainly, but they do not by their nature represent an unpredictable event that could do harm to the organization. What I am referring to are those risks which could significantly alter the direction of the organization, especially in pursuit of its strategic vision. One example in the nonprofit social service area would be the attempt by a labor union to organize direct support professionals. Another might be the damage caused to the reputation of the organization by the sexual abuse of a client. Trust me, there are a hundred and one ways in which a nonprofit organization can be damaged by an unforeseen event. Understanding the nature of risk, planning scenarios to address various risks, developing plans to mitigate those risks – these are all critical activities that are directly related to the organization’s ability to achieve its strategic vision. Integrating risk assessment and management into the strategic planning process will help the organization become and remain adaptable in the face of uncertainty.

I would strongly encourage every nonprofit to seriously attend to this issue, and if lacking in knowledge or expertise in this regard, hire someone to facilitate that process. The point I wish to make here is that I have not seen any nonprofit organization integrate risk assessment into its strategic planning process. And by this I do not mean conducting a SWOT analysis. I do not consider weaknesses and threats, per se, to necessarily be risks to the organization. They are factors to be managed, certainly, but they do not by their nature represent an unpredictable event that could do harm to the organization. What I am referring to are those risks which could significantly alter the direction of the organization, especially in pursuit of its strategic vision. One example in the nonprofit social service area would be the attempt by a labor union to organize direct support professionals. Another might be the damage caused to the reputation of the organization by the sexual abuse of a client. Trust me, there are a hundred and one ways in which a nonprofit organization can be damaged by an unforeseen event. Understanding the nature of risk, planning scenarios to address various risks, developing plans to mitigate those risks – these are all critical activities that are directly related to the organization’s ability to achieve its strategic vision. Integrating risk assessment and management into the strategic planning process will help the organization become and remain adaptable in the face of uncertainty.

Well, that’s my laundry list of some things to consider when undertaking the next comprehensive strategic planning process. I am currently writing a longer-length article which lays out in more detail what a model might look like which incorporates these factors. I’ll keep you posted when it is available.

In the meantime, if you would like to discuss the strategic planning process in your organization, please give me a call. I’d love to chat about how some of my thinking in this regard might help you and your organization plan for a preferred future.

Recommended Sources on Strategic Planning, Sustainability, and Strategy:

Allison, Michael and Jude Kaye. (2015). Strategic Planning for Nonprofit Organizations. 3rd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Bell, Jeanne, Jan Masaoka and Steve Zimmerman. (2010). Nonprofit Sustainability. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

LaPiana, David. (2008). Nonprofit Strategy Revolution. New York, NY: Fieldstone Alliance.

McLaughlin. Thomas (2006). Nonprofit Strategic Positioning. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.