So begins the journey into self-discovery and planning your preferred future.

I have been mildly surprised to hear nonprofit clients tell me, “We don’t have to mess around with reviewing the mission statement. Our board just went through that exercise. We’re fine with our current statement. Let’s just get on with writing a strategic plan.”

I certainly don’t wish to denigrate the efforts of CEOs and boards to evaluate their organizations’ mission statements, but the strategic planning process really does need to begin with a careful analysis of what the organization is doing, with whom, how, and why. Ideally, these questions have already been answered in a pithy, one sentence statement. It’s just that I’ve seen too many organization’s treat this exercise as nothing more than a necessary but annoying task that boards periodically conduct. On the one hand, it may be viewed as an opportunity by a few to contrive a grandiloquent slogan. On the other hand, the exercise may be greeted with disdain as if it has no relevance to what the organization does. One college president told me, “We don’t need a mission statement. Our mission statement is what we do every day.”

Let me suggest that “mission” for a nonprofit organization is the same as “profits” for private sector companies. Thought of in this manner, having a clear and effective mission statement for a nonprofit is as important as knowing product demand for a for-profit company. “If mission accomplishment is as important as profit attainment, why do most nonprofits not spend equivalent time in mission creation and monitoring? In reality, nonprofits often completely mess this up. As important as missions are, nonprofits frequently go off in ineffective directions by relying on mission statements that can be little more than slogans” (Pandolfi, 2011).

So, in the interest of launching strategic planning at the correct starting point, indulge me for a few minutes as I dig a little deeper into this first question: “What are you doing?” It seems to me that the starting point for strategic planning must be a consensus understanding of what the organization strives to accomplish by fulfilling its mission. Conversely, failure to seriously address the organization’s mission not only can undermine the strategic planning process, but will likely contribute to ambiguity of purpose in the minds of significant stakeholders. Without careful analysis of the organization’s mission, strategic planning itself will likely become an unprofitable academic exercise incapable of providing the focus and discipline needed to achieve the organization’s preferred future.

To understand the significance of such an analysis, consider a few mission-related questions: Why was your organization founded? Who started it and why? Are you doing the same thing today that the founders did on day one? With whom do carry out your mission? Do you serve the same population? What will this population look like in the future? Who supports your mission? How do they perceive your mission? What impact is your mission having? Can you demonstrate that you are fulfilling your mission? Can you measure the impact it has on the target population? What do you think your mission will look like in five or ten years? Is your mission sustainable? The mission statement of a nonprofit organization is the critical starting position from which to answer all those questions and upon which to build strategies to proactively prepare for the future.

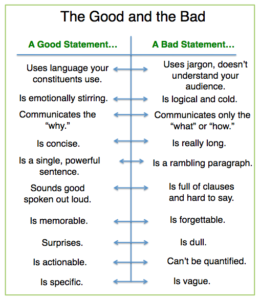

So what is a mission statement and what are the attributes of an effective mission? Koenig suggests that every good mission statement has three pivotal elements:

- Our cause: Who? What? Where?

- Our actions: What we do.

- Our impact: Changes for the better.

He goes on to graphically illustrate the attributes of good and bad mission statements (figure 1).

(figure 1)

The most effective mission statements are written in a single sentence of 15 words or fewer and contain all three of those elements. Here are a few examples to make the point.

- Public Broadcasting System: To create content that educates, informs and inspires.

- Environmental Defense Fund: To preserve the natural systems on which all life depends.

- CARE: To serve individuals and families in the poorest communities in the world.

- And of course, TED: Spreading ideas.

More than just serving as an inspirational slogan that employees and donors can get behind, Pandolfi argues that “an effective mission statement must be a clear description of where an organization is headed in the future that distinctly sets it apart from other entities and makes a compelling case for the need it fills.” In other words, there are critical business reasons tied to the organization’s strategy. In the same way that a clear and effective strategy in the private sector attracts more customers which result in more profit, a nonprofit’s clear and effective strategy facilitates attraction of funds and provides the ability to take smart action.

And if you think mission statements are old fashioned, consider this. Recent research at Ohio University shows that Millennials especially are drawn to a strong mission. “Young employees want to believe their work is making a difference, whether they are in the for-profit or nonprofit sector. Good mission statements place the organization in the wider social context, and show how the work of the organization contributes to making society a better place” (Fritz).

An effective mission statement also allows a nonprofit organization to operate with focus and discipline by providing consistency in decision-making. It also suggests the means for measuring success and creates a shared understanding among all stakeholders that transcends time and place. In other words, an effective mission statement is translatable into measurable actions that everyone in the organization can understand, monitor, and influence.

One might also ask the question: “What would the world look like if we actually fulfilled our mission?” Would hunger cease? Would discrimination be eradicated? Would every child succeed in school? Contemplating such “mission exits” should lead organizations to think deeply about how they measure their success. A good mission statement should suggest what that world would look like if completely fulfilled.

Finally, I believe that the process of creating a mission statement is of equal importance to the end result. In the nonprofit world, boards of directors are the caretakers of the mission. CEOs are hired to advance the mission and make sure it is carried out. Staff are directed to manage processes which support the mission. Donors provide financial support for the cause described by the mission. All these participants have a stake (hence, the term “stakeholder”) in the success of the organization, either morally (boards, donors and volunteers) or practically (staff who are paid for their services). Engagement of all these stakeholder groups in the creation/review/analysis of the mission statement is one of the most effective ways available to build support and loyalty.

Finally, I believe that the process of creating a mission statement is of equal importance to the end result. In the nonprofit world, boards of directors are the caretakers of the mission. CEOs are hired to advance the mission and make sure it is carried out. Staff are directed to manage processes which support the mission. Donors provide financial support for the cause described by the mission. All these participants have a stake (hence, the term “stakeholder”) in the success of the organization, either morally (boards, donors and volunteers) or practically (staff who are paid for their services). Engagement of all these stakeholder groups in the creation/review/analysis of the mission statement is one of the most effective ways available to build support and loyalty.

As a consultant, ever eager to serve my nonprofit clients, I have found it occasionally challenging to insist that the process begin with a thorough discussion and review of the organization’s mission statement. Invariably, however, when such a review conducted, it serves as the foundation to developing a robust and effective strategic plan.

Once the organization is clear about what it does, it can proceed to do a deeper dive into the remaining nine questions. Up next week: How well are you doing?

References Cited:

Fitz, Joanne. How to Write an Amazing Nonprofit Mission Statement. (online article at: https://www.thebalance.com/how-to-write-the-ultimate-nonprofit-mission-statement-2502262. (January 20, 2017)

Koenig, Marc. Nonprofit Mission Statements – Good and Bad Examples. (online article at: https://nonprofithub.org/starting-a-nonprofit/nonprofit-mission-statements-good-and-bad-examples/.) (2013)

Pandolfi, Francis. How to Create an Effective Non-Profit Mission Statement. Harvard Business Review. March 14, 2011)

A strategic plan can be thought of as a story. It has a past, a current reality, and a future that has yet to be written. In other words, a strategic plan provides a narrative context for understanding the organization and its movement into a desirable future. Because the story is still being written, it is sometimes useful to step back and ask a few simple questions in order to establish meaning and purpose for the activities that comprise strategic planning. I have found these questions to be particularly helpful with boards of directors who may not always see the complexity of organizational processes or have the capacity to digest large quantities of information. While there are myriad tools, systems, methods and models of strategic planning, not all of them address all of these foundational questions. My experience has shown me that any plan that doesn’t somehow answer these questions does not serve the organization well.

A strategic plan can be thought of as a story. It has a past, a current reality, and a future that has yet to be written. In other words, a strategic plan provides a narrative context for understanding the organization and its movement into a desirable future. Because the story is still being written, it is sometimes useful to step back and ask a few simple questions in order to establish meaning and purpose for the activities that comprise strategic planning. I have found these questions to be particularly helpful with boards of directors who may not always see the complexity of organizational processes or have the capacity to digest large quantities of information. While there are myriad tools, systems, methods and models of strategic planning, not all of them address all of these foundational questions. My experience has shown me that any plan that doesn’t somehow answer these questions does not serve the organization well.

I’d like to believe that the large majority of CEOs have a solid circle of such friends who can help them maintain sanity and balance in their personal and professional lives. I just don’t happen to know too many. And I certainly wasn’t one of those fortunate few, either. I wish I had been. My experience has shown me that CEOs have a great need for holistic support from others who care deeply for them and who can provide honest, trustworthy and confidential advice. But this requires a certain amount of vulnerability, something which doesn’t come naturally for many executive leaders. As one of my spiritual guides, Fr. Richard Rohr, recently wrote:

I’d like to believe that the large majority of CEOs have a solid circle of such friends who can help them maintain sanity and balance in their personal and professional lives. I just don’t happen to know too many. And I certainly wasn’t one of those fortunate few, either. I wish I had been. My experience has shown me that CEOs have a great need for holistic support from others who care deeply for them and who can provide honest, trustworthy and confidential advice. But this requires a certain amount of vulnerability, something which doesn’t come naturally for many executive leaders. As one of my spiritual guides, Fr. Richard Rohr, recently wrote: To address this need for growth and support through vulnerability, some CEOs hire an executive coach to provide objective, dispassionate advice and counsel. That’s fine at the professional level, but doesn’t usually address personal issues. Others utilize the services of a psychotherapist to manage emotional challenges. Still others use a spiritual guide with whom they can “confess.” I even know of one retired CEO who for years had his own private board of directors. This was a relatively small, diverse group of individuals who held him accountable in every aspect of life. Their pledge for total confidentiality only cost him several dinner meetings each year – a very small price to pay for the benefit he derived. He told me that he both looked forward to and dreaded those meetings. They made him better. They kept him whole. And they made him accountable.

To address this need for growth and support through vulnerability, some CEOs hire an executive coach to provide objective, dispassionate advice and counsel. That’s fine at the professional level, but doesn’t usually address personal issues. Others utilize the services of a psychotherapist to manage emotional challenges. Still others use a spiritual guide with whom they can “confess.” I even know of one retired CEO who for years had his own private board of directors. This was a relatively small, diverse group of individuals who held him accountable in every aspect of life. Their pledge for total confidentiality only cost him several dinner meetings each year – a very small price to pay for the benefit he derived. He told me that he both looked forward to and dreaded those meetings. They made him better. They kept him whole. And they made him accountable.