The strategic plan you have just completed tells a story. It provides a setting with historical background, location, conflict, challenges and exciting opportunities. There is definitely a plot line with plenty of foreshadowing and suspense. There are characters who play critical roles in the story. Most of all, your story can evoke strong feelings of loyalty and support. Those who encounter your story should be moved emotionally, should connect with the characters and their cause, and should be inspired enough to share the story with others.

If you think I am exaggerating with this attempt to analogize between a strategic plan and a story, I would suggest that you are ignoring the power of narrative in influencing the affective psyches of the people who are connected to your organization. Believe me when I tell you that your strategic plan has the potential to influence the attitudes of funders, enhance employee loyalty, evoke satisfaction among your clients, inspire respect in the minds of competitors, and build support from your board of directors.

A good strategic plan sends a powerful message to constituents that you have a compelling mission, that you understand your environment, that you are visionary and forward thinking, that your organization has the capacity to change and move into the future, and that you know where you are going. Telling that story in the right way to the right audience for the right reason is the final step in this ten-part approach to coherent strategic planning.

You may ask, “How can a strategic plan, complete with charts and tables and lists and goals and all manner of other technical information, be told like a story?” The answer is that the form and substance of the story depends on the audience.

You may ask, “How can a strategic plan, complete with charts and tables and lists and goals and all manner of other technical information, be told like a story?” The answer is that the form and substance of the story depends on the audience.

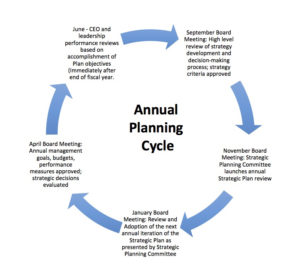

For the board of directors and the executive leadership team, the strategic plan as a whole is the story. It has to be assumed that individuals in these two leadership areas require the story in its entirety in order to properly execute their responsibilities. Therefore, printing the entire document (please, not in four-color glossy brochure format!) for use by leadership is necessary if you intend to use it on a regular basis to guide discussion, frame decisions, evaluate progress, and celebrate accomplishments. I would argue, in fact, that the strategic plan should be printed and included in each quarter’s board briefing book and that agenda items for board discussion be drawn from the strategic plan. To avoid having the plan die a dusty death on somebody’s shelf, it must become the operating manual that guides all activity.

Because typical strategic plans can get rather lengthy and detailed, how can the story be told to employees, donors, volunteers, clients and others in a way that accomplishes the purposes I’ve listed above? I’d like to offer a few suggestions for your consideration. Not all of these may be appropriate for your organization, but I hope you will be able to gain some ideas on how to tell your story. Just keep uppermost in your mind the needs of the audience you are seeking to communicate with and the form of the story will take its own shape appropriately.

- Print the organization’s mission, vision and core value statement in poster-sized format and post them throughout the facilities. A little money spent to have this done professionally will communicate to those who see them that the organization places a lot of value in these statements as guides for action and descriptors of the corporate ethos.

- Print the Position and Goal statements in a similar poster-sized format and post them alongside the mission, vision and core values posters. It may be sufficient to just publish the position statements. However much detail is provided, they must be easily readable and must communicate the big picture direction the organization is taking.

- Publish a “precis” of the strategic plan, i.e., a two or three pages executive summary that can be printed in small booklet form to use with donors, volunteers and others. In such an abbreviated form of the plan, marketing and communications staff will want to reframe the strategic plan into a readable narrative that engages the reader and leads to some type of conversion, be it a donation, greater commitment, volunteering, or other types of engagement.

- Depending on the audience, such a brochures or marketing materials may or may not be supported by colored graphics and a professional layout. The question driving those decisions should be: “Will this document in this format significantly support the purpose for which it is intended with the intended audience?” Some would argue that slick four-color expensive brochures can turn off committed donors who might question spending money on an expensive marketing piece. Others will argue, however, that doing it right communicates serious commitment to the vision and is essential for attracting new donors.

- My mentor once described the role of CEO as “chief story-teller.” If the organization has the capacity to post videos (e.g., through YouTube, vimeo, or other formats) to employees and others, the CEO might consider a short five-minute video in which he/she talks about the strategic plan and what it means.

- In addition to mission, vision and core value statements, one organization I worked with posted each year’s initiatives, their tactical annual action plans, throughout the organization to help employees understand better why certain decisions were made and why actions were taking place.

- Organizations which are centrally located and hold annual “town hall” meetings – either for staff or clients – should consider devoting one such meeting to the strategic plan and what it means for them. Such high-level presentations are great for soliciting feedback and for better understanding of issues that might impede progress.

- The strategic plan should be prominently exhibited on the organization’s website. However, I would recommend against posting annual initiatives, key performance indicators, and other data that might be either too technical, confidential, or subject to interpretation. The organization’s media, marketing and communications staff should work with leadership to post a narrative version of the strategic plan that is user readable and attractive. The heart of the strategic plan is comprised of the position and goal statements and these should be most prominent in any online presentation. How much of the back story and analysis should be included is a judgment call, but in my view, should be kept to a minimum.

- For tech-savvy organizations, many opportunities exist for mounting social media campaigns around the strategic plan, posting various positions and goals, and inviting comments and support. Those with active intranet systems, discussion boards using programs such as SharePoint can serve to further embed the strategic plan goals into the life of the organization. Similarly, board book platforms can promote discussion in and around board meetings, giving opportunities for directors to engage in generative discussions related to strategic issues.

- Organizations which are dispersed could consider holding focus group sessions in remote locations to explain the plan and its implications for the company in its various locations. Ideally, such focus groups should be held before the final plan is rolled out to promote ownership of dispersed stakeholder groups. I used this tactic to great effect when I was facilitating a strategic plan process in the context of a merger. Stakeholders in the acquired company gained access to the CEO and became insiders and participants in the planning process, making sure that their regional concerns were heard.

Organizations engage in comprehensive strategic planning in order to identify and achieve their preferred future. The strategic plan, told as a story, is intended to generate support and commitment to that future. Whether that is in the form of money, time, ability, loyalty, or respect – the story is told with a deliverable in mind. Suffice it to say, the story of the strategic plan, artfully shared, can go a long way toward helping the organization achieve its preferred future.

I would love to hear about your experiences in how you communicated your strategic plan to your constituents. Feel free to leave comments and reactions.

If you would like to explore further ideas on how to tell your story, please call or email me. I would welcome the opportunity to discuss (with no obligation on your part) any aspect of this article or those that preceded it.

And of course, I am always available to discuss how I might be of service to you in achieving your preferred future.