How Can the CEO Help the Board Stay Focused on Sustainability?

One of the most neglected areas of concern for nonprofit boards is the issue of whether or not the organization they have been called to govern has the capacity to sustain itself under current conditions and whether the organization is positioned to deal with future changes in the operating environment. It is sometimes assumed that if the board is attending to the commonly accepted duties and responsibilities for nonprofit boards, sustainability will be the natural byproduct of effective and efficient board functioning. In one sense that might true, so far as the board is capably monitoring the finances, conducting strategic planning, and overseeing the work of the CEO. On the other hand, these functions, though essential, do not necessarily require the board or the CEO to think strategically about mission sustainability.

At the outset, I should note here that by sustainability I am not talking about environmental sustainability. For many businesses, this has come to mean the implementation of green strategies in order to become more environmentally neutral. While I am a strong advocate of using renewable energy and finding ways to reduce a company’s carbon footprint, I am focusing this article on the financial and missional sustainability of a nonprofit organization. That isn’t to say there aren’t possible points of intersection between these two understandings of sustainability, but my immediate concern here is in making sure that an organization can continue to survive and thrive in executing its mission.

With this qualification in mind, sustainability, as I have come to use the term, is the ability of an organization to fulfill its mission in an impactful way and in such a manner that financial and human resources are sufficient to continue its work. This definition entails much more than profitability, the term most often associated with sustainability. And it is much more than the delivery of high quality and impactful services. Obviously, if an organization can’t produce a positive bottom line, it will go out of business no matter how noble the cause or critical the need. The old saw: “No money, no mission!” is a commonly accepted truism. From a fund-raising perspective the opposite is also true: “No mission, no money!” In the nonprofit world, therefore, sustainability requires both sufficient resources and an impactful mission to succeed.

Let me give you an example at the program level to show you what I mean. Working with a recent church client, we examined several social ministry programs which were supported by the contributions of members, one of which was a homeless shelter and meal program. Because of declining congregation membership and commensurate declines in contributions, the cash reserves of the homeless program were being steadily depleted. Moreover, there existed several comparable programs within a mile radius of the church which operated larger and more effective programs. Even though there was strong leadership and some support in the congregation for maintaining the homeless program, it was clear that if the program was going to continue, it would need to find new sources of revenue. It would also need to implement a number of changes in order to distinguish itself among similar organizations. Failing to do so would diminish its ability to raise funds. You can see from this example how a diminishing source of money, combined with perceived lack of mission impact and mediocre quality could contribute to a downward spiral and eventually lead to closure of the program.

This is such an important distinction for the CEOs and boards of nonprofit charitable organizations to understand. The large majority of such organizations were founded to meet human needs and to address underlying social problems. Around the world, this altruism found expression in the form of hospitals, nursing homes and social ministry organizations that served the poor, disabled, homeless, hungry, imprisoned, marginalized, abused, traumatized, addicted, and mentally ill. They were very often launched by religious organizations and churches and required volunteers and contributions to make them work. In the United States, over time, government financial support in the form of Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, government and foundation grants, Medicare and other forms of financial support replaced individual donors, providing stability on the one hand but also imposing restrictions and regulations on the other. Today, many nonprofit organizations, having replaced fund raising with grant writing, are vulnerable to the vagaries of government largesse. In the organization of which I was the CEO, 85% of our revenues came from Medicaid.

One could argue that sustainability is the overarching responsibility of organizational leadership and that all other duties and responsibilities are necessary to support the board’s efforts in this regard. In the context of this series of articles entitled “Who’s the Boss?,” the role of the CEO is critical in both helping his or her board see and accept this ultimate duty and in providing executive leadership with the board to make sure they exercise their responsibilities to this end.

To advance the argument that sustainability is ultimately the primary duty of both CEO and board, I propose in this article to describe three aspects of sustainability and demonstrate how the CEO’s executive function is essential for the board to fulfill its duty in this regard. I will consider how sustainability can be defined, measured and reported and how such information must feed into strategic plans and discussions leading toward the organization’s preferred future. I will also discuss the importance of capacity assessment and how it can evaluate the organization’s internal structure and ability to support sustainability processes and initiatives. Finally, I will talk about risk management in the context of organizational sustainability, especially as potential threats to the organization might damage its ability to continue its mission of service.

Some authors include a number of other factors that help support organizational sustainability. These include resource development (i.e., fundraising), succession planning, collaboration, and other strategic decision-making processes. Others focus on marketing, the use of social media, public relations, and visual communication. A few mention the importance of creating an understandable value proposition in order to persuade supporters that they are receiving a return on investment. A few of these are listed among the references that follow this article. These other factors are certainly worthy of discussion as they relate to sustainability but, because I have addressed them in depth in other articles in this series, I have chosen not to include them here. In my experience, the three components I have described can stand by themselves as the principal indicators of sustainability.

Impact and Profitability

In order to examine the role of the CEO in helping the board focus on sustainability, it is first important to provide a workable definition which can focus efforts in this regard. For purposes of this article, I prefer to think about nonprofit organizational sustainability in the terms used by Zimmerman and Bell (2015). They argue that sustainability should be thought of in terms of both mission impact and profitability and they provide a methodology for calculating the same. I have used their model in strategic planning work in order to answer the question, “How well are we doing?” For those interested in their methodology, I highly recommend their book, Sustainability Mindset. However, there are other ways in which the broad categories of mission impact and profitability can be computed and analyzed to arrive at a measure of sustainability. I will speak in general terms about these variables and how they can be used by CEOs and their boards.

Beginning with “mission impact” it is important to set aside the question of “Are we fulfilling our mission?” This question, most often asked at the beginning of vision-setting or strategic planning workshops is superficial at best and misleading at its worst. The large majority of nonprofit organizations I have encountered have noble missions which are carried out faithfully by staff through programs that serve the populations I described above. For the most part, such a question is a “drive-by” question that very few could not check. The brief conversation would go along the lines of the following:

Board: “Do we have a good mission statement?”

CEO: “You bet!”

Board: “Are we serving the people we want?

CEO: “Yes, we are.”

Board: “Are they pleased with the services we provide?”

CEO: “Yes, for the most part.”

Board: “So then, are we fulfilling our mission?

CEO: “Absolutely!”

The problem with such thinking, however, is that it does not look beneath the hood of the organization to determine the extent to which the fulfillment of the mission is having the desired impact on the population it serves. Sure, it can honestly say it is fulfilling its mission, doing what it says it exists to do, but it does not begin to get at how well the organization is carrying out its mission and the extent to which it is really serving its clients. To answer that question, much deeper analysis is required. Questions should be asked which reflect the complexity of the impact construct. For example:

- How does each program contribute to overall mission impact?

- How well (i.e., level of excellence) is each program executed?

- Which factors contribute to a program’s impact on the population it serves? Area? Size? Staff? Funding?

- How deep and profound is the change in people’s lives that comes about as a result of the program?

- How broadly does the program serve; how many people does it touch?

- Does the program address a significant unmet need in the community or is there a lot of competition?

- Does the program leverage its impact to build support and collaboration from others?

- Does the program help or hinder the overall reputation of the organization?

- Does the program attract volunteers and donors?

There are numerous ways in which answers to these questions can be obtained. CEOs and their boards should think deeply about how best to measure mission impact. Several organizations I have worked with used online surveys to compile an overall measure of impact. Zimmerman and Bell have offered free tools which can assist in this effort. However, smaller organizations with more limited resources might wish to conduct interviews with key stakeholders or develop their own rating scales for the most applicable questions. Regardless of how mission impact is measured, some type of rating or ranking system for determining program impact should be used. The reason for this will become apparent later. Such an impact rating system should describe each program in relation to the others provided by the organization.

A brief word should be inserted here about how one should define a “program.” A program, as I have operationalized the term, is any unit of discrete activities aimed at providing mission-related services to the population identified in the mission statement. Some of these should be obvious. A senior services agency would have programs such as assisted living, memory care, skilled nursing, chaplaincy, and the like. However, also included in the definition should be activities such as fund-raising, including major giving, planned giving, fundraising events, grant writing, and others which, although not offering direct client support, communicate the organization’s mission to contributors and others who make the mission-related programs financially possible. Therefore, a program is any set of activities that serve people or which enable such services to be provided.

In determining which approach to measuring mission impact is used, how data is to be gathered, and which constituents and stakeholders are going to be involved, the CEO plays a key leadership role with the board. First of all, the whole endeavor of calculating and reporting sustainability should not be relegated to the pile of “administrative duties” performed solely by the CEO. Because the questions posed have to do with the extent to which the organization is fulfilling its mission, the board, which “owns” the mission must be integrally involved in measuring its impact. Of course, the CEO is in the best position to recommend methods and processes for calculating sustainability and for proposing strategic responses that might result from the analysis, but the idea I have advanced for “reciprocal governance” begs for the collaborative and mutually supportive roles of both the CEO and the board. Regardless of the methodology for calculating impact, there must be consensus between the CEO and his or her board about is meant and how it is going to be measured to make sure that both have confidence in the process and the results.

The second aspect of sustainability is financial profitability. At first glance, one might be tempted to think that this is very simple to measure. All that is required is comparing program revenues to program expenses to see if it makes money or loses money. The challenge comes from trying to identify the true costs of a program. Every program has direct expenses such as the costs of transportation, meals for clients, supplies for group homes, salaries for nursing staff, etc. However, everything a program does in carrying out its mission has other costs associated with it. Each program also has shared expenses that are used by multiple programs. These can include expenses such as utilities, technology, insurance, salaries of administrative functions such as the full-time equivalent time spent on programs by the CEO, HR, finance and other offices. These expenses are most often assigned to programs on an allocation basis and are usually based on the size of the direct expense budget of each program. There are also administrative costs which are allocated across all program areas which include things like external accountants, board expense, legal costs, etc. Careful thought should be given to the allocation method used to make sure that shared and administrative costs are accurately represented.

One of the most difficult aspects of calculating true cost is the allocation of staff salaries. Of course, some staff are assigned exclusively to a single program, such as direct support professional or nurse assigned exclusively to a specific program. Other positions are more challenging. How full-time equivalent (FTE) positions are assigned across all programs takes some discussion and thoughtfulness. For example, executives responsible for cross-organizational functions like finance, HR, IT, marketing, and operations provide time and service to all programs. How the time of executives and their staffs are allocated must reflect the actual average amount of time they spend supporting each program.

Eventually, the organization must come up with a reasonable number which reflects the true cost of operating the program. The sum of all these true program costs should add up to the organization’s total operating budget. Profitability, therefore, is defined as the revenues raised or allocated for the program (either internally or externally), minus the true costs of operating the program. Both the total amount of the true cost (direct, shared and administrative costs) and the net profitability (revenues minus true cost) should be recorded. The reason for this should be obvious and can be illustrated by several scenarios. A program may be net neutral but may consume a large percentage of the organization’s resources. Another program my lose money (is not profitable) but is a very small expense to the organization. It may be core to the mission or is a loss leader for other services.

When combined in a matrix or bubble chart or some other visual presentation, the mission-impact analysis over against the profitability data will give the organization a clear picture of sustainability. Four possible scenarios present themselves within which gradations can be made:

- The best possible scenario is when a program is both profitable and has a high impact on mission fulfillment. It is very rare in the nonprofit world to find such programs, but they are out there. A summer camp may show a net profit and be perceived as providing the highest quality experience to its campers. An adult-education provider might charge enough tuition to be profitable and offer an outstanding learning experience. However, most charitable organizations which are involved in human services are not so fortunate, especially if they are dependent upon government funding or gift revenues to meet minimum service requirements.

- The second scenario is one in which the large majority of nonprofit charities find their programs, namely, they have high mission impact but they cannot cover their total true costs. They can be thought of as the heart of the organization, but they lose money. To ensure financial viability, therefore, they must offset the loss from operations with non-operating revenue such as that which comes from fundraising efforts.

- The third scenario usually applies only to fund raising activities that are not directly mission-related, but which are necessary to cover operating losses. These activities can be thought of as the money tree or cash cow and should be supported to keep “heart of the organization” programs functioning. Attention should be paid, however, to how much its costs the organizations to support these efforts. In other words, monitoring the “cost to raise a dollar” is very important to overall organizational sustainability.

- The final scenario is one in which a program is neither profitable nor provides the quality or impact expected by clients. From a strategic point of view, such programs represent a threat to long term sustainability and should be evaluated for either elimination or, if not feasible, then investment to improve both profitability and impact.

From this description of how sustainability can be measured, the CEO, working collaboratively with his or her board, can address key strategic questions. Of the high-impact, profitable programs, which can we expand or replicate? Of the high-impact, unprofitable programs, which can we make more profitable, either by raising additional gifts or fees or by cutting expenses? Of the low impact, unprofitable programs, which can we eliminate? Which can we work with to improve quality? Which can we make profitable? And finally, of the low-impact and high profitability programs, which can we add or grow to generate even more revenue? Of these programs, are there those with high “costs-to-raise-a-dollar” that could be improved or replaced with more efficient and effective programs?

In exercising his or her executive responsibilities vis-à-vis the board of directors in regards to sustainability, the CEO will want to have command of the data for the profitability of all programs, the missional impact of those programs, the relationship between these two variables, and an understanding of the possible strategic moves that can either increase impact or improve profitability. Thinking of sustainability in these terms requires the CEO to demonstrate leadership with his or her board in order to ensure their understanding of how well the organization can continue to carry out its mission and the actions that might be necessary to enhance its sustainability.

Capacity

The second aspect of sustainability is the overall capability of the organization to continue its programs and services. This is a different issue than profitability and mission impact because it is related to the leadership and management functions and processes that undergird and support all mission-related activities. In my experience working with nonprofit agencies of different types, capacity assessment is one of the most neglected activities by CEOs and their boards and is also one of the most important analytic functions they should perform. I will briefly discuss a number of different functions which are critically important to mission effectiveness and profitability and without which most nonprofits will struggle.

Before discussing the other various aspects of organizational capacity, I’d like to first examine the importance of leadership and in this context, the leadership provided by the chief executive officer. Throughout this series, I have argued that the CEO has an executive duty to the board in order to support a culture of reciprocity in leadership and governance. When it comes to organizational capacity, however, I will state unequivocally that the success of any organization always comes down to the leadership effectiveness of its chief executive. If organizations succeed and thrive, it is because of effective leadership. If they decline and fail, it is because of poor leadership. Leadership is everything. The best board in the world can’t function effectively with an inept chief executive. On the other hand, an outstanding executive will always find ways to work, even with an incompetent board of directors. Therefore, it is imperative for the board of directors to have in place processes which evaluate the leadership effectiveness of their one employee, the CEO. I have discussed this in a previous article, but with respect to organizational capacity, this issue must lead the discussion.

The second area to consider in this regard is the mission of the organization. A good mission statement is more than just a slogan. It is a statement of the organization’s raison d’etre and should be translatable into everything the organization does, including the supporting functions and processes that support missional programs. Do all staff in the organization know what the mission is? Is the mission statement referred to frequently when discussing programs and services? Is the mission statement a guide for strategic decisions? Does the mission statement permeate all activities, plans, procedures and policies? If an organization is ambiguous about why it is in business and about whom it serves, uncertainty about direction and diffusion of focus are likely to occur. CEOs and their boards should regularly evaluate the mission statement to make sure it reflects the best current and most relevant thinking about what it chooses to do. Having a powerful and relevant mission statement is the platform upon which the other areas of capacity are built.

A third aspect of capacity is the organization’s culture. Every group of people organized to perform some function or service has a culture, that is, they have their own norms, rules, language, tools, beliefs and attitudes that contribute to the group ethos. Nonprofit organizations, regardless of size, also have a corporate culture. Understanding the culture and how it effects the ability of the organization to function effectively is critically important for the CEO and the board. Regardless of how it is measured or how it is evaluated, organizational culture is a strong determinate of success and mission fulfillment.

As an example, in the organization of which I was the CEO, we determined that the prevailing culture among employees was seriously at odds with our philosophy of client services. While we used “people first” language in the person-centered planning we used for the persons with disabilities we supported, long-standing HR policies and draconian practices with employees led to the treatment of staff as commodities to be used and expended and not as human beings with worth and dignity. Over several years, we worked to bring the culture of employment into alignment with the culture of client services. Any organization that has acquired or merged with another company has also had to deal with differences in organizational culture. The point I’m trying to make is that organizational culture can either work toward or work against mission attainment and should be assessed periodically to make sure it is in alignment with organizational values.

The fourth aspect of capacity has to do with governance. It isn’t necessary to examine this aspect of capacity in any depth since I have treated the roles, responsibilities and relationships of the board in previous articles and have suggested ways in which the organization’s governance can be assessed. Suffice it to say, it is a critical dimension of what we call capacity. Strong and supportive boards can promote mission advancement, while poorly equipped or dysfunctional boards can impede progress. To support long term sustainability, the capacity of the board should be assessed.

The fifth aspect of capacity I would like to examine is that of planning. Most often, organizations think of planning as that long-range, comprehensive strategic planning effort that is undertaken every three to five years. While I have argued that long-range, strategic planning has value as a scaffold for overall organizational action, the recent COVID-19 pandemic and associated quarantine and restrictions on public gatherings underscore the importance of having strategic decision-making processes in place that support nimbleness and responsiveness to rapidly changing environmental conditions. I address the importance of such capacity for strategy development in my book, Your Preferred Future. Achieved. (pp. 71-82) and have examined the role of the CEO in leading his or her board in the planning effort in a previous article.

The sixth area consists of all those activities that comprise the resource development or fund-raising capability of the organization. I know of very few nonprofit agencies that can fund all their expenses with operating revenues and which don’t need some sort of charitable support to maintain their operations. This aspect of capacity assessment should inquire about the efficiency of fund-raising, usually by analyzing the cost to raise a dollar. Size of staff, the nature, type and effectiveness of fund-raising activity (e.g., direct mail, events, auctions, golf outings, major gift and/or capital campaigns) should be evaluated. A strong fund-raising function can help offset ups and downs in operating revenues and can help build endowment or other reserves. These are critically important to long range sustainability.

Although not usually considered as part of overall organizational capacity, the systems, processes and controls utilized by the organization to regulate behaviors are very important and can either support or damage sustainability. This seventh area of consideration is of paramount importance for any nonprofit. An organization which has highly developed and clearly delineated systems and procedures in place for handling and processing revenues and expenses is much less susceptible to abuse or misuse of funds. How expenses are handled, how invoices are processed, which banking and payroll systems are used, and how staff processing of receivables and payables relate to each other, are all significant contributors to sustainability. First, such processes help the CEO and board accurately report the financial condition of the organization, but second, they can alert the leadership to trends in financial performance that might diminish sustainability. Such systems promote a culture of stewardship and financial responsibility. Other systems such as protocols for decision-making and approvals ensure consistency and rationality.

The eighth area of capacity consists of all the policies and procedures that govern how employees and directors work in relation to their duties and to each other. Besides the financial controls previously mentioned, policies and procedures around employment, operations, fund-raising, marketing and communication, should be crafted to ensure consistency and integrity in all operations. When ambiguity exists in how policies are executed, people will conclude that those executing policies are arbitrary. To ensure coherence and consistency, policies and procedures should be periodically reviewed, perhaps even to the point of scenario testing with panels of representative staff and other constituents. However it is done, the CEO should make sure that the organization’s policies and procedures reflect the mission and values of the organization and are fair to all concerned.

The ninth aspect of capacity has to do with employees, how they are hired, retained, compensated, promoted – in short, all the human resources services and practices that are aimed at obtaining and maintaining a qualified and motivated staff. Mission sustainability in the human services is largely dependent upon the people providing the services. Therefore, a significant component of organizational capacity has to do with making sure the right people are hired to do the right thing in the right position. Keeping such people motivated and supported should be the primary goal of any human resources function.

The tenth aspect of capacity covers the entire area of physical assets and consists of properties, buildings, furnishings, infrastructure, information technology, equipment, vehicles and all other capital property that is used to support the programs and services of the organization. You can imagine the challenge a nonprofit charitable organization might face, no matter how noble its mission and how essential its services, if facilities are shabby and in disrepair, vehicles are broken down and rusty, computers are unreliable, roofs leak – well, the list could go on and on. Facilities which are attractive, well-maintained and highly functional support a positive public image and attract clients. Equipment which is up to date and regularly serviced ensures consistency of program support. Information systems and equipment that are regularly updated and maintained are vital to smooth operations. Vehicles that are on a rotation system for replacement ensure safety and positive image. Properties that have high curb appeal with well-groomed yards, paint and siding that are fresh, and lighting that enhances both security and aesthetics – all these represent investments that promote sustainability and should be considered part of the organization’s capacity.

An eleventh area of capacity follows and supports the foregoing. Marketing and public relations functions are critically important to develop support for sustainability in a number of areas. When working collaboratively with the fund-raising function, marketing and public relations should enhance development activities by producing attractive and effective supporting literature and media materials. When working with operations, these functions can support client recruitment and retention. They can also enhance employee morale by presenting materials to staff that communicate quality and the importance of staff roles to the success of the organization.

Finally, a twelfth dimension of sustainability, advocacy, is utilized by some nonprofit agencies to obtain support for clients, seek changes in public policies that affect clients or staff, or which seek to gain additional rights for the people supported by the agency. Capacity in this regard is measured by the human and financial resources the organization has committed directly to support this endeavor. In the human services area, organizations whose mission is to provide services and support for marginalized or under-served populations have an ethical responsibility to serve as the voices of those who can’t speak for themselves. Overall organizational capacity is affected by the amount of support that can be gained through advocacy efforts.

How can capacity be measured? There are numerous scales, inventories, rating systems and other tools available for CEOs to measure capacity. At one time, McKinsey supported an outstanding online assessment tool (Organizational Capacity Assessment Tool) that evaluated every one of the items I described above. Unfortunately, they no long support the OCAT and no other organization has picked up its rights. However, there are many other sources of good tools and inventories to assess organizational capacity. There are both online and paper/pencil tools to choose from. I described some of these in my book, Your Preferred Future. Achieved. (pp.57-62), in which I advocated conducting capacity assessment as an important aspect of strategic planning. Whichever tool CEOs and their boards decide to use, and I am not recommending any one over another, it is critically important to have a clear understanding of the organization’s ability in these areas to support the mission and programs of the organization.

Most usually, the CEO and the board together determine who should participate in such an assessment. From my experience, as many individuals as possible who have a sufficient working knowledge of these twelve areas should be asked to respond or participate. If an inventory or survey is conducted, a sufficient number should be sought to ensure data reliability and generalizability. If interviews or paper and pencil surveys are conducted, concern for staff time and skill in processing and interpreting the results should be considered.

Besides the impact and profitability of programs and services, organizational capacity is the biggest contributor to long term sustainability and should be regularly assessed.

Risk Management

The third dimension of sustainability I would like to explore in this article has to do with those things that can pose a threat to sustainability. If threats can be managed and mitigated, then sustainability can be supported. In this section I will describe what I mean by risk, how risks can be identified and operationally defined, and suggest a process for assessing and managing risk factors to the organization.

Early in my career as a CEO, an incident occurred which impressed upon me and my board the importance of risk planning. One of our area directors had been remiss in reporting the results of negative site evaluations. When we received notice that our license to operate in a particular state was in jeopardy of being pulled, we had to scramble significant resources to correct the deficiencies, appeal our case, deal with management shortcomings, and make sure our programs were back on a solid footing. To satisfy state officials, we actually had to contract with an independent management firm to reorganize the area’s operations. In short, we came within a hair’s breadth of losing our programs in that state.

When all this was reported to our board, including what had happened, the steps we were taking to correct the problem, and what it was going to cost the organization in the long run, a question was asked that greatly influenced my thinking around risk and sustainability. One board member stated it this way: “How will you make sure this never happens again?”

Threats to an organization can come from just about anywhere. Having the capacity to react to negative events is one thing. Anticipating and preparing for possible threats is entirely another. What our board member wanted to know was, have you anticipated that this type of thing could occur and what are you doing proactively to minimize the likelihood of it occurring again?

Some organizations rely upon their insurance carriers to provide risk management strategies. This is particularly true in the area of workers compensation coverage. Insurance companies, of course, have a vested interest in reducing claims due to workplace injury or work-related illness. Trainings from companies focused on these types of incident are good, but do not typically address the wide range of potential threats I am discussing here.

Risks, threats and challenges can come from any or all of the areas listed above under the category of capacity. They may reflect adverse changes or events in leadership or governance. They may be the result of employee misconduct. They may come from physical property and its damage or loss, from erosion of funding, loss of program licensure, system and procedure failures, adverse publicity, or even lawsuits due to discriminatory practices. To be prepared for negative or adverse events is the essence of risk management. To have strategies in place for reducing possible threats comprises risk mitigation. Being prepared and equipped to deal with myriad threats and challenges is a very important functional aspect of organizational sustainability and the CEO has a duty to lead his or her board of directors in comprehending and supporting risk management efforts.

How can all the possible risks be identified? A starting point might be to go back through the twelve components of capacity and ask “In this area, what could possibly go wrong?” Leadership teams representing different levels and roles in the organization could be assembled to brainstorm possible areas of risk under each category. The CEO could engage the board through its Audit Committee to review the list and offer suggestions. Eventually, the organization should have a well thought out list of the most realistic and likely incidents or conditions that pose the greatest threats to the organization.

To give you an idea of possible risks and how they can be stated, I have listed a number of possible scenarios or conditions under each capacity.

- Leadership

- Loss of the CEO

- High executive turnover

- Whistleblower complaints

- Mission

- Ambiguous or misunderstood mission

- Program inconsistency

- Culture

- Misalignment of values

- Negative subcultures

- Inconsistent leadership

- Governance

- High board turnover

- Board/CEO conflict

- Dysfunctional board meetings

- Planning

- Lack of strategic plan

- Lack of decision-making process

- No operational plans

- Resource Development

- Decrease in gift revenue

- High cost to raise a dollar

- Shrinkage of endowment

- Systems, Processes and Controls

- Embezzlement of funds

- Unauthorized spending

- Mismanagement of debt

- Policies and Procedures

- Role conflicts among staff

- Discrimination lawsuit

- Rogue manager

- Employees

- High staff turnover

- Unionizing effort

- Employee misconduct

- Physical assets

- Property loss

- Vandalism

- IT system crash/data loss

- Marketing and Public Relations

- Bad press

- Poor public image

- Client abuse

- Advocacy

- Loss of government funding

- Adverse public policy decisions

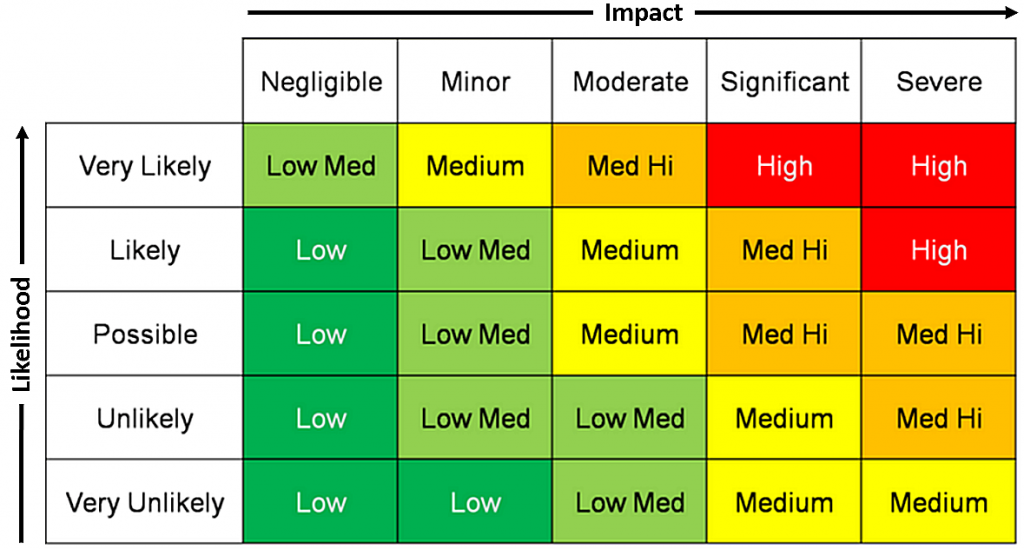

Once agreement is achieved around the specific real risks to the organization, the list should be further refined by adding two qualifiers to each risk: first, what is the probability of the risk event actually happening and second, if the risk event should occur, what is the potential harm or negative impact the event would have. Obviously, the intent of this exercise is to identify those risks which are of highest likelihood and which have the greatest potential for damage to the organization. A commonly utilized visual model of risk is in the form of a chart in which each possible risk is shown with the probability of occurrence as low, medium or high, and the potential damage or harm shown as low, medium or high. Those risks identified as having the highest probability of occurrence with the highest potential for harm should be the targets of serious analysis and strategizing in order to either reduce the probability or minimize the harm. An example of such a matrix is shown below.

Identifying risks is only the first step in managing risk. It is one thing to have a nice, color-coded chart which shows the organization’s risks. It is another to develop plans to both minimize the likelihood of adverse events occurring and which detail response actions to minimize the negative impact of an adverse event when it happens. In my organization, we developed a detailed chart of plans which identified the staff member with primary responsibility for the risk, the status of both mitigation and management plans, and timelines for completion of activities aimed at reducing both probability of occurrence and negative impact.

Managing risk factors is a critically important function which falls under the leadership of the CEO and his or her executive team. Making sure that the Board understands the risks and, more importantly, supports the management and mitigation efforts of the staff, is a key executive responsibility of the CEO. How this is accomplished varies according to the size and complexity of the organization. In my own case, our board had a powerful audit committee that had oversight of finances, ethical practice, whistleblower complaints, human resources management and risk management. I and my team provided quarterly detailed reports which updated risk factors and our progress toward positioning the organization to deal effectively with those challenges.

Conclusion

Organizational sustainability is a complex issue involving numerous elements and factors. Sustainability requires ensuring the highest quality and greatest impact on the people supported by the organization’s programs and services and making sure that programs are financially profitable in the sense that operating, gift and investment revenues are sufficient to support them. It requires the organization’s investment in capacity to make sure that people, systems, assets, policies and practices are obtained and organized to optimally support the mission. Finally, sustainability requires an awareness of the risks faced by the organization and an up to date plan for managing and mitigating those threats.

Because of the complexities involved in ensuring organizational sustainability, the CEO must carry the majority of responsibility for leading this effort with his or her board of directors. In my experience, boards can be great resources for developing and supporting sustainability, but they cannot and should not be involved in the actual work of ensuring sustainability. In this regard, the CEO must exercise executive leadership in reporting data around the various facets of sustainability (i.e., quality, profitability, capacity measures and risk), providing analysis and assessments for the board, offering proposals and recommendations to further support sustainability in every respect, and in general, to make sure the board understands and is conversant with the various facets of sustainability and their ultimate duty in this regard. Such reciprocal governance is the optimal merger between management and governance, between leadership and oversight, and between executive and legislative functions.

References

Alexander, Geoff. The Nonprofit Survival Guide: A Strategy for Sustainability. (2015). McFarland and Company, Inc. Jefferson, NC.

Bowman, Woods. Finance Fundamentals for Nonprofits: Building Capacity and Sustainability. (2011) John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Emmanuel, Jean-Francois. Financial Sustainability for Nonprofit Organizations. (2015). Springer Publishing Co., LLC. New York, NY.

McMillan, Dennis T. Focus on Sustainability: A Nonprofit’s Journey. (2013)

Rasler, Tom. ROI for Nonprofits: The New Key to Sustainability. (2007). John Wiley and Sons. Hoboken, NJ.

Yarbrough, Jennifer. The Journey from Nonprofit Startup to Sustainability: Principles and Best Practices to Leaving a Legacy of Community Impact. (2019). Rhonda’s Writing and Publishing Firm.

Zimmerman, Steve and Bell, Jean. The Sustainability Mindset: Using the Matrix Map to Make Strategic Decisions. (2015). Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.